Lula Is Running Huge Budget Deficits and Scaring Off Investors

(Bloomberg) -- It’s been almost two years now since Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva secured his return to power in Brazil. For investors, they’ve been bleak. The currency is down, government bond yields are up and the stock market has only eked out half the gains posted across the rest of emerging markets.

Most Read from Bloomberg

A Floating Island in Baltimore Raises Hope for a Waterfront Revival

‘Train Lovers’ Organize to Support Harris and Walz in Presidential Bid

Part of Downtown Montreal Is Flooded After Water Pipe Breaks

All this stands in stark contrast to Lula’s first presidential stint two decades ago. Back then, he became the unlikeliest of Wall Street darlings — a radical union leader who shocked pundits by quickly embracing fiscal austerity — and oversaw a furious rally in the country’s markets. The main stock index posted average annual gains —in dollars — of 38% during his eight years in office.

The global backdrop was very different then. Prices for raw materials that Brazil produced were soaring, pulling an ever-growing stream of dollars into the nation, and global interest rates were at rock-bottom levels, pushing investors to seek out risky assets that could generate higher returns in places like Brazil. Now, commodity prices are flat at best, and interest rates are at the highest in generations in the US and elsewhere.

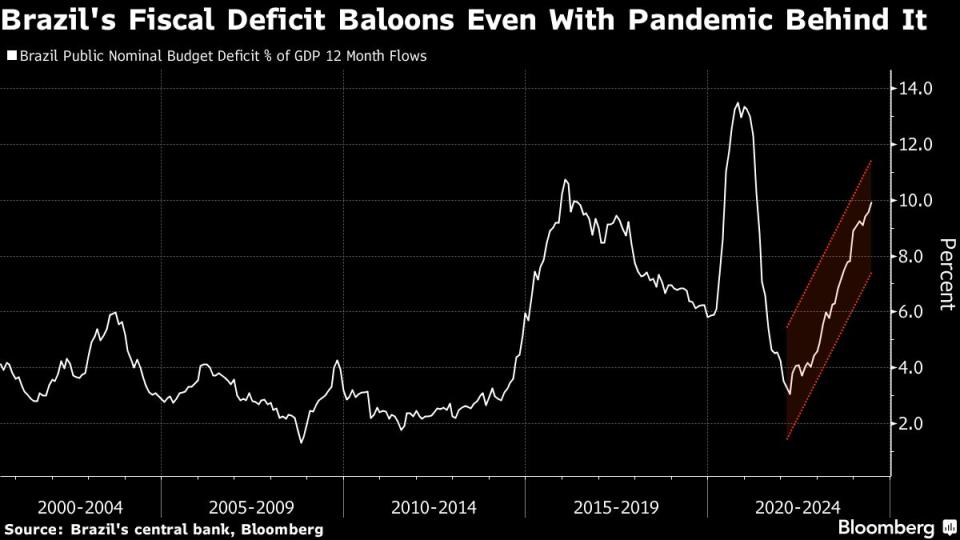

The president doesn’t seem to have caught on to — or care much about — this new reality. The Lula of 2024 shares little in common, Brazil watchers say, with the Lula of 2003 who was hellbent on proving he wasn’t the profligate spender his critics said would wreck the Brazilian economy. He’s balked repeatedly at calls for spending cuts to rein in a budget deficit that has ballooned to the equivalent of about 10% of Brazil’s gross domestic product.

It’s a staggering figure, far bigger than any deficit posted in his first go-round and one of the largest in the world. And it’s driving away investors who were already hesitant to sink money into an emerging-market economy when they can earn more than 5% on a US T-bill or, for that matter, double-digit stock returns off the AI frenzy generated by Silicon Valley.

“It took us a while to appreciate the magnitude of the fiscal slippage, but now we fully recognize it and are not optimistic,” said Patrick Campbell, a portfolio manager at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. “It’s just been all about spending. The malaise is completely generalized.”

Brazilian markets have stabilized some of late, with the currency and stock market posting gains over the past couple weeks. This year’s losses remain deep, though. The Ibovespa stock gauge has slumped 11% in dollar terms; the real has fallen 11% against the dollar, more than any other major currency; and yields on benchmark fixed-rated bonds have surged more than 1.9 percentage points.

Lula, of course, doesn’t need to cater to investors. But by ignoring their concerns, he risks further choking off the flow of capital, deepening the slide in the currency and fanning a new inflation spike that would hurt all Brazilians.

The central bank has warned the worsening inflation outlook could force it to start raising benchmark interest rates again as soon as next month. At 10.5%, they’re already among the highest in the world, squeezing highly indebted companies and crimping economic growth.

“Brazil has been unbelievably noisy,” said Patrick Esteruelas, the global head of research at hedge fund EMSO Asset Management in Miami. “It’s hard to develop a lot of conviction amid constant political interference in fiscal and monetary policy.”

A government spokesperson said Lula has made clear in recent public statements how committed he is to controlling spending. Among them was an interview last month in which he said he was “more serious about fiscal responsibility than anyone who opines about it in Brazil.”

A spokesperson for his finance minister, Fernando Haddad, said the slide in local stocks in the first half was due to a selloff in risk assets and that they are outperforming peers since Lula returned to office. Markets are getting more positive on the fiscal outlook, the ministry said, citing a government report from mid-August.

Brazil’s role in global markets has diminished greatly since the boom years, which only heightens the risks for Lula. The country’s weighting, for instance, in MSCI’s main emerging-markets gauge has fallen in half over the past two decades to 4%, a reflection of its declining share of global economic output and moribund capital markets. There hasn’t been a single IPO in the country in the past three years. That MSCI weighting is just a third of South Korea’s and less than a quarter of India’s.

It’s become easy, in other words, for investors to ignore Brazil. And they have. Today, the country’s stocks trade at a 26% discount to their 10-year average.

“When I started my career doing emerging markets, you needed to allocate a lot of your thinking to Latin America and to Brazil,” said Ted Mann, a senior emerging-markets analyst at Ariel Investments in New York who started covering the region in 2013. “Now it’s gotten much, much smaller. And I think that direction is likely to continue.”

Those who remain bullish on Brazil point to, among other things, the fact that the Federal Reserve is about to start lowering interest rates, which should help drive money back into emerging markets. Optimism those cuts will start next month helped spark the recent rebound in Brazil assets.

“This is probably the wrong time to get bearish about Brazil,” said Geoffrey Dennis, a retired Wall Street strategist. Dennis first started analyzing Brazilian markets in the early 1990s and follows them closely to this day. The one caveat to his optimism: “unless we start to see a lot more bad fiscal decisions.”

For a while it looked like Lula was going to take steps to clean up the fiscal accounts, just like he had two decades earlier. He pushed a new cap on spending and a long-awaited tax reform through Congress, and the country won two credit-rating upgrades in his first year in office.

But cracks were already starting to show. Lula publicly criticized the nation’s newly independent central bank, pressuring policymakers again and again to lower rates faster to bolster growth.

Then in April, his administration tweaked a key budget target, paving the way for higher spending. Markets posted some of their steepest losses of the year in the days that followed. Brazilian hedge funds remain bearish today. They’ve been shorting local assets or shunning them entirely, according to monthly letters to investors, and shifting a growing slice of money into offshore assets.

“The fiscal outlook is the No. 1 risk at home,” said Priscila Araujo, a portfolio manager at O3 Capital in Sao Paulo. “Brazil can clearly benefit from a more favorable global backdrop as the Fed starts cutting but some additional measures need to be implemented if it wants to tackle fiscal concerns.”

--With assistance from Giovanna Bellotti Azevedo, Leda Alvim, Davison Santana, Simone Iglesias and Martha Beck.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Singapore's Wooden Building of the Future Has a Mold Problem

Inside Worldcoin’s Orb Factory, Audacious and Absurd Defender of Humanity

Surgeons Cut a Giant Tumor Out of My Head. Is There a Better Way?

Sports Betting Is Legal, and Sportswriting Might Never Recover

New Breed of EV Promises 700 Miles per Charge (Just Add Gas)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.