Higher rates and inflation, lower growth present different opportunities for investors

I see the bad moon a-risin’

I see trouble on the way

I see earthquakes and lightnin’

I see bad times today

Don’t go around tonight

Well it’s bound to take your life

There’s a bad moon on the rise

~ Creedence Clearwater Revival

Prior to the global financial crisis of 2008, if you had asked me what would happen if the United States Federal Reserve and other central banks slashed rates to zero and then left them there for more than a decade, I would have told you that it wouldn’t be long before the world faced a serious inflation problem. I would have been dead wrong.

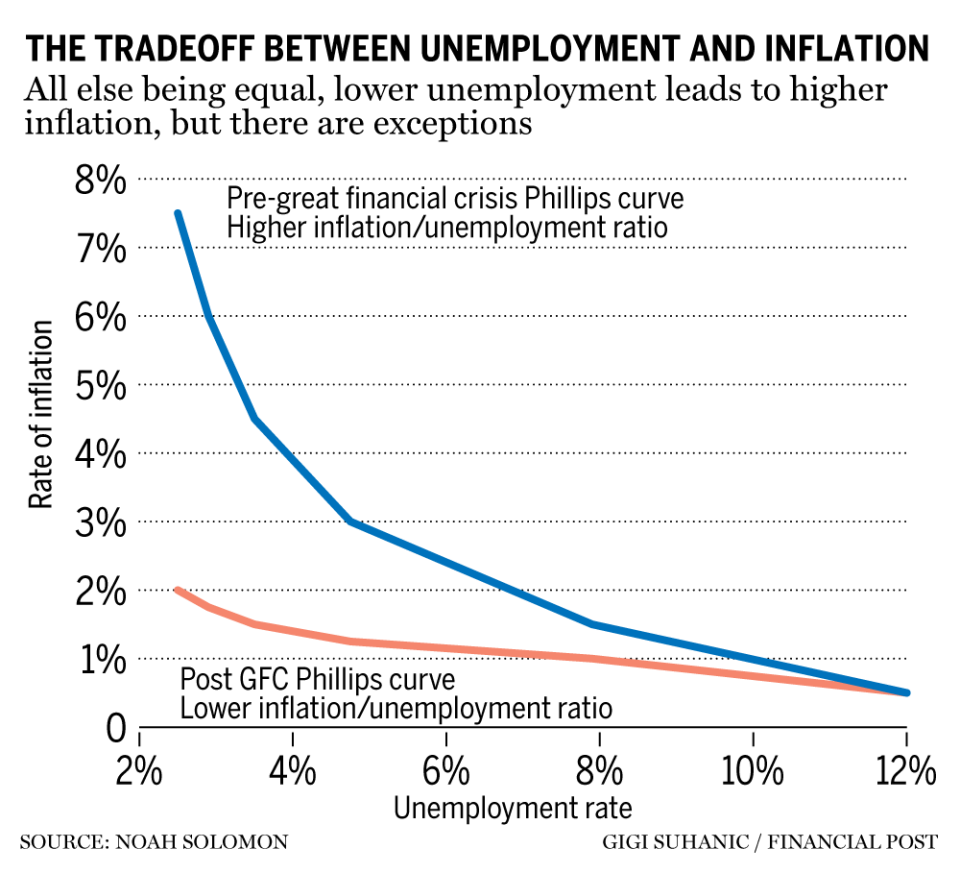

The Phillips curve is an economic concept developed by William Phillips that states there is an inverse tradeoff between unemployment and inflation. All else being equal, lower unemployment leads to higher inflation, while higher unemployment is associated with lower inflation.

This theory proved largely resilient for most of the postwar era. However, a notable exception occurred in the years following the global financial crisis (GFC). From 2009 to 2021, despite unprecedented amounts of monetary and fiscal stimulus and record-low unemployment, global prices remained unexpectedly subdued.

In the years following the GFC, the Phillips curve seemed to have shifted downward, allowing central bankers to leave rates at uber-stimulative levels for an extended period without spurring inflation. This dynamic remained in place until 2021, when COVID-19-related stimulus and supply chain disruptions caused an acceleration in prices, forcing central banks to aggressively raise rates.

Declining rates: How do I love thee?

Low interest rates make it easier for consumers to borrow money for purchases, thereby increasing companies’ sales volumes and revenues. They also enhance companies’ profitability by lowering their cost of capital and making it easier for them to invest in facilities, equipment and inventory.

Lower rates also result in higher multiples, from elevated P/E ratios on stocks to higher multiples on operating income from assets such as real estate.

“Interest rates power everything in the economic universe,” Warren Buffett has said. “They are like gravity in valuations. If interest rates are nothing, values can be almost infinite. If interest rates are extremely high, that’s a huge gravitational pull on values.”

The effects of disinflation-induced higher earnings and higher valuations cannot be overestimated. Using monthly data, the S&P 500 posted an annualized return of 18 per cent from the GFC low at the end of February 2009 through the end of 2021, which is roughly double the index’s long-term average.

Perhaps the single most important factor that enabled the extended Goldilocks environment of strong growth, low unemployment and scant inflation was a dramatic increase in global integration and trade.

In the 30 years from 1991 through 2021, total international trade rose to 57 per cent from roughly 37 per cent of global gross domestic product, largely propelled by the consistently rapid growth of the Chinese economy coupled with its rapid integration into the global economy.

There were other factors that kept a lid on inflation. In particular, advances in technology undoubtedly played a part. But the China effect has been a significant contributor to disinflation in the post-GFC era. However, this deflationary influence is either slowing or reversing outright.

Populism, politics and deglobalization

Anti-trade rhetoric has become increasingly prevalent, most notably between the United States and China. Whereas Democrats and Republicans seem unable to agree on whether the Earth is round or flat, there is nonetheless bipartisan support for tariffs and other trade restrictions.

The likelihood of greater global economic integration in the foreseeable future has also been reduced by a rash of geopolitical conflicts, which have caused companies to re-evaluate supply chains and explore nearshoring opportunities. “Just in case” is replacing “just in time” as the guiding principle for companies seeking to fortify their supply chains.

Meanwhile, China’s population is rapidly aging, which is contributing to a growing labour shortage. Its working population shrank by 38 million over the 10 years ending in 2020. In contrast, the number of those aged 65 and older increased by 60 per cent. Relatedly, Chinese wages have doubled since the GFC.

Given that China lies at the heart of global production and accounts for roughly 20 per cent of the world’s working-age population, rising wages in “the world’s factory” will hinder its historical disinflationary influence and could push price levels up globally.

Most major economies are also experiencing a deterioration in the ratio of their working-age populations to retirees. In The Great Demographic Reversal, London School of Economics professor Charles Goodhart argues that aging populations will spur inflation. Specifically, he believes older people will continue to consume goods and services even as their retirement contributes to labour shortages.

Investment implications

While these developments do not mean that rates cannot decline from current levels, they do suggest the neutral setting for monetary policy (the rate that is neither inflationary nor restrictive) may be higher than what markets have grown accustomed to.

A long-term shift towards a lower-growth/higher-inflation/higher-rate regime carries significant implications for markets and portfolio positioning. In particular, such a change would usher in an interruption or outright reversal of many of the longstanding investment themes and outperformers that have characterized markets over the past several years.

The darlings of yesteryear, which include private equity (PE), venture capital, tech stocks and other long-duration growth assets, are unsurprisingly the very same asset classes that benefited the most from an unusually favourable mix of strong growth and low rates.

By the same token, their future prospects will be most affected by a reversion to a more normal macroeconomic environment. Consequently, investors might be well-served to reduce their exposure to PE, venture capital and growth stocks in favour of value stocks and high-quality bonds.

Noah Solomon is chief investment officer at Outcome Metric Asset Management LP.

_____________________________________________________________

If you like this story, sign up for the FP Investor Newsletter.

_____________________________________________________________

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.