Is the economy headed for a hard or soft landing? Music fans think ‘recession pop’ has the answer.

The stock market crashed. The unemployment rate soared. But the music slapped.

That’s at least what Joe Foster, 27, remembers when he thinks of the Great Recession: nights spent drinking Sprite at under-18 clubs in the London suburbs, dancing to Lady Gaga and Kesha and the Black Eyed Peas.

Most Read from MarketWatch

In fact, there may be an explicit link between those euphoric pop tracks and a suffering economy, Foster argues in one video posted to his TikTok page.

“A wise man once told me that two signs that we are headed into financial ruin is No. 1, all of the strip clubs are empty,” he explains in the clip, which has more than 90,000 views. “No. 2, the pop music is brilliant.”

That latter claim is the argument behind “recession pop,” social media’s new moniker for the category of dance-y pop hits that dominated radio stations in the years following the 2007-’09 financial crisis.

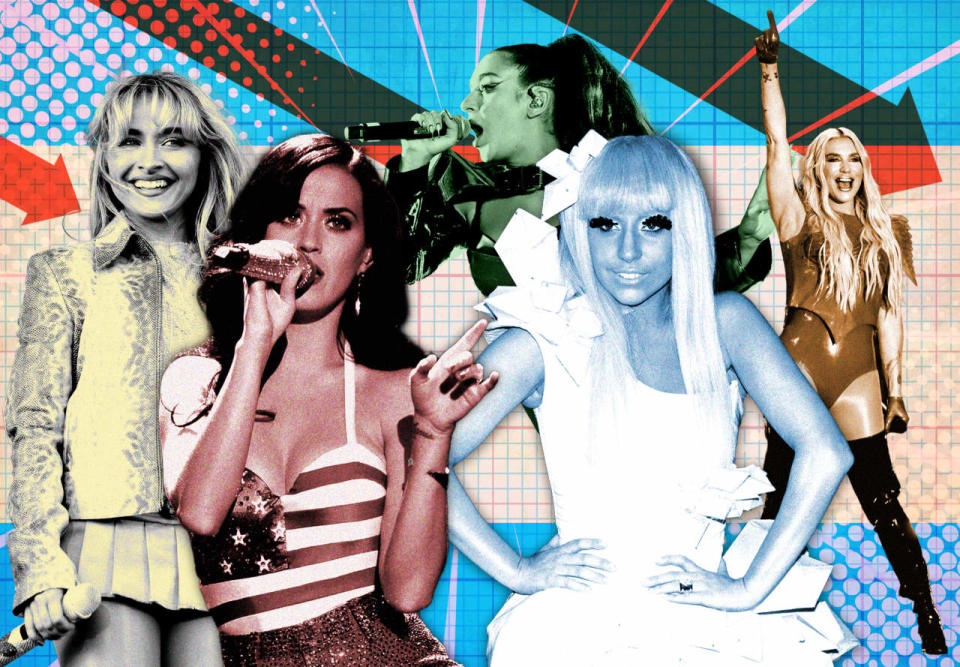

You won’t find the subgenre listed in history or music textbooks. But on TikTok, “recession pop” refers to a collection of songs that, in hindsight, seem perfectly designed to distract listeners from the financial woes of the period: Think LMFAO ordering that “everybody just have a good time” in 2011, when nearly one in 10 Americans was out of work, or Lady Gaga telling us to “just dance, it’ll be OK” as home prices cratered in 2008.

As the term has gained traction this year, so has the theory that a struggling economy can lead to great music — or that great music could hint at harder times ahead. The high unemployment rate and falling home values of the Great Recession gave us the frothy hits of Kesha and Katy Perry, recession-pop theorists argue.

Similarly, they say the rising rents and gloomy economic vibes of 2024 have created the perfect conditions for Chappell Roan’s campy, dance-along “Hot to Go!” and Charli XCX’s “brat,” on which the artist labels herself a “365 party girl.”

In other words: Pop music is getting good again, the theory goes. And that’s proof that we’re headed for an economic downturn — if we’re not in one already.

As recession anxieties have roiled Wall Street, there’s a chance that those armchair economists are on to something.

“If there ever was the time for recession music it’s post-pandemic in a cost of living crisis,” one user wrote in a comment on a video claiming the genre is making a comeback. “Give us the escapism club pop.”

Or, as another commenter put it: “The harder the times, the better the music.”

How the economy influences music

The idea at the core of the recession-pop concept does have some empirical backing.

When times are tough, people flock to positive music, a pair of recent studies from economists at the University of Alcalá in Spain found. The first analyzed Billboard Hot 100 hits from 1958 through 2019 and found that when unemployment is high, listeners are more drawn to music with positive lyrics and upbeat tempos. A second paper found that trend continued during the distress of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a two-month recession in the U.S.

Other macroeconomic indicators, including stock prices and the inflation rate, can also affect musical preferences, the researchers found.

“Society tends to use positive music as a self-comforting tool when macroeconomic conditions are bad,” Juan de Lucio, a co-author of the studies, told MarketWatch.

In the same way that consumers spend more on small luxuries like lipstick during a downturn, de Lucio said, economic conditions can also influence the culture we consume.

That link between economics and art is evident in modern music history — though it might have as much to do with the economy’s influence on musicians as it does with those listening to their songs, said Joe Bennett, a forensic musicologist at Berklee College of Music in Boston.

“Artists and songwriters are human beings,” Bennett said. “They’re not working in a social vacuum.”

In times of trouble, “music tends to go one of two ways,” he said. “You can narrate it: You can write lyrics about being sad and miserable and economically disempowered,” he said. “Or you can say, what the hell — we’re all poor. Let’s party.”

A look at the last century offers plenty of examples of that dichotomy: In 1932, a year in which nearly a quarter of Americans were out of a job, Bing Crosby topped the charts with “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” The song tells the story of an American everyman who finds himself destitute, waiting in a bread line during the Great Depression.

In the popular film “Gold Diggers of 1933” just one year later, Ginger Rogers sang “We’re in the Money,” a track that fantasizes about a return to riches.

“We’re in the money, the sky is sunny,” the chorus repeats. “We’ve got a lot of what it takes to get along!”

When tight monetary policy triggered an economic downturn in the early 1980s, Billy Joel chronicled the demise of a Pennsylvania manufacturing town in “Allentown,” which spent 22 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100.

During that same period, Kool & The Gang urged listeners to “celebrate good times” on their No. 1 hit “Celebration.” That song came out in 1980, a year in which the inflation rate reached 14.6%.

Even so-called recession pop between 2008 and 2012 had its antithesis, Bennett said: As Americans danced to Far East Movement’s “Like a G6” and Pitbull’s “Give Me Everything,” Adele and Ed Sheeran charted with more sobering lyrics on “Rolling in the Deep” and “The A Team,” respectively.

It’s hard to say whether pop music can offer clues about the future of the economy, said Charlie Harding, a music journalist, songwriter and co-creator of the podcast “Switched on Pop.” But for the last century at least, it’s clear that the economic reality has influenced music.

“People were responding to uncertainty through music,” he said. “But I think they always have.”

Is recession pop an actual music genre?

That being said, “recession pop” can’t really be considered its own genre — at least not in traditional terms, music experts told MarketWatch.

“It’s essentially a label that mashes up a style with a timeline,” Bennett said.

The songs that TikTok users have labeled “recession pop” do seem to have a few key characteristics in common, experts said. MarketWatch used these shared qualities to build the recession-pop playlist linked at the top of this article: mostly upbeat, danceable pop songs released between 2008 and 2012 with a maximalist production style and carefree lyrics.

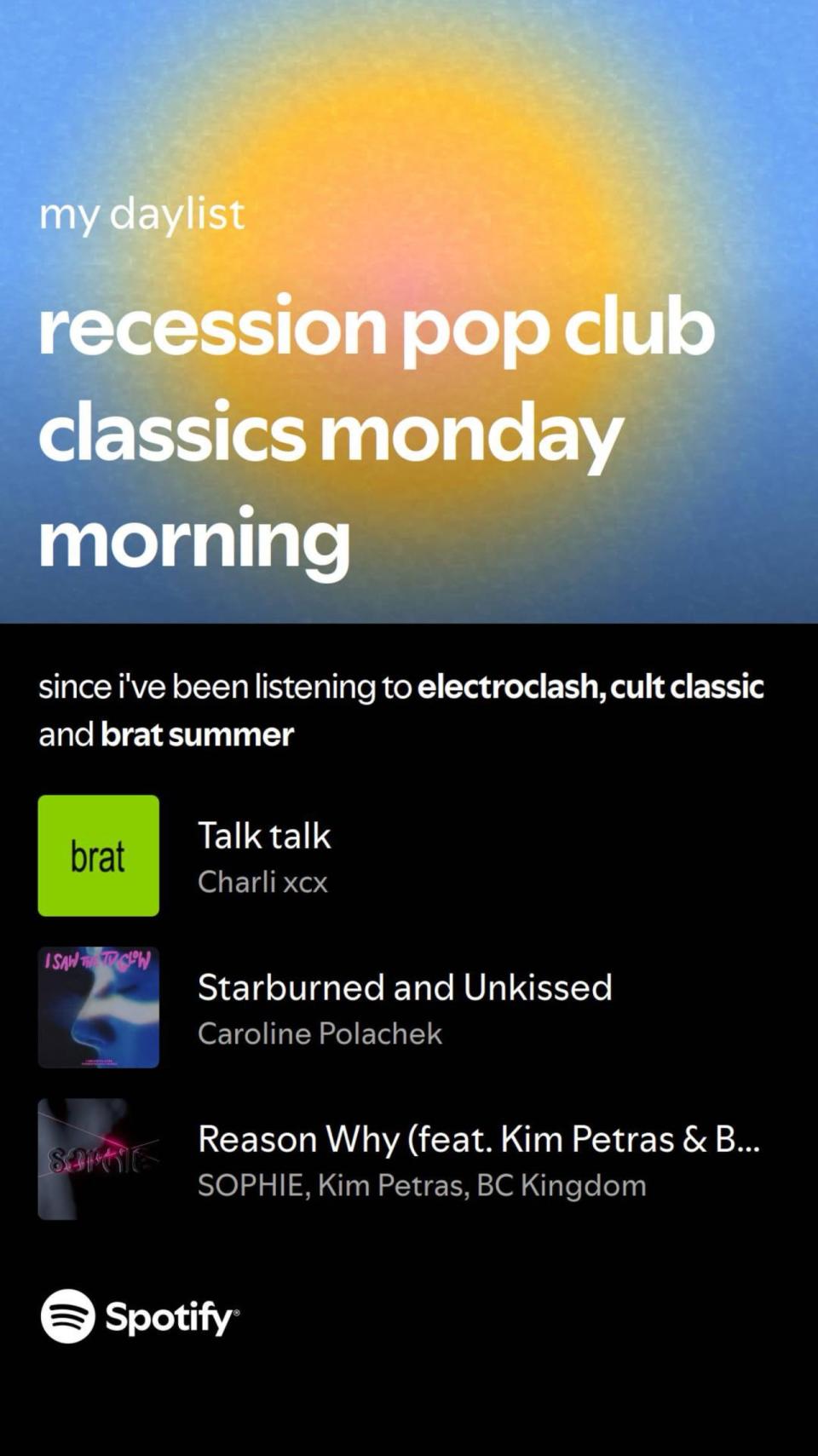

On Spotify SPOT, the streaming platform is recommending the “recession pop” genre to some listeners on its “daylist,” a daily autogenerated playlist based on users’ listening habits.

“New genre names or groupings, like ‘recession pop,’ are created to map to emerging genres or reframe familiar ones, making them more recognizable and relevant for listeners,” a Spotify spokesperson told MarketWatch in a statement.

The rise of recession pop might have less to do with a definable musical style than it does a resurgence of nostalgia among social-media users. Like Foster, those who were in middle or high school during the Great Recession era are entering their late 20s and early 30s — prime years for reflecting on the soundtrack of their youth.

“There’s a certain maxim in the music community: All the best pop music in the world came out in the same year, and it’s the year that you were 17,” Bennett said. Music from 12 to 16 years ago is just about old enough to enter that nostalgia cycle, he said.

About that recession

If recession pop is indeed back in vogue, it’s missing the first half of its namesake. By most traditional measures, the U.S. economy isn’t in a recession right now.

But lately, the country’s economic future hasn’t been so certain. A weaker-than-expected jobs report stoked fears that the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates too high for too long, slowing growth for longer than necessary.

Those concerns helped spur a market meltdown last Monday that sank stocks and left investors spooked. Stocks rallied Thursday, with the S&P 500 index SPX clocking its best day since 2022, while investors remained laser focused on what upcoming inflation data will reveal.

Even without the traditional recession warning signs, many Americans have felt for months that they are falling behind. Persistently high prices have pinched budgets, especially for the lower half of earners. In many metropolitan areas, rents have shot up by double-digit percentages since the start of the pandemic. A slowing white-collar labor market is making it harder for workers, especially young people, to find a well-paying job.

For some Americans, those are the kinds of economic circumstances that make escapism sound appealing.

Pop music has helped fill the void before. But Foster, the TikToker, wonders if a new era of recession pop — economics aside — could ever top the original.

His favorite track from the category is “Club Can’t Handle Me” by Flo Rida and DJ David Guetta. It’s an exuberant track about the unshakeable high of a good night out — one that hit No. 9 on the charts in 2010, one year into the recovery from the worst economic crash of this century.

They just don’t make music like that anymore, Foster told MarketWatch.

“It makes me a little emotional,” he said. “People long for those big moments again.”