(Bloomberg Opinion) -- All upheavals leave their marks. Some fade away, some linger. Following the Black Death, the plague that’s believed to have killed 60% of Europe’s population in the second half of the 14th century, the realization that life is short, played a big role in shaping interest rates in late medieval Europe, stretching all the way to the Enlightenment.

Could we witness very long-term effects from the present contagion?

The coronavirus pathogen isn’t as deadly as bubonic plague, and our toolkit for dealing with pandemics is far better stacked than when the pestilence reached the harbor of Messina on the northeastern coast of Sicily in late 1347. But while the dislocation caused by the respiratory disease has had a catastrophic impact on commodity and asset prices, a recovery may not close the chapter. The coronavirus, too, could leave a durable imprint.

Economic historians quibble over the exact consequences of the Black Death, though they agree that the sudden depopulation had a dis-inflationary impact. Workers’ productivity shot up because previous generations were eking out little extra output from finite land. Now they were gone; the Malthusian trap, in which growth was constrained by limited food supply, had sprung open.

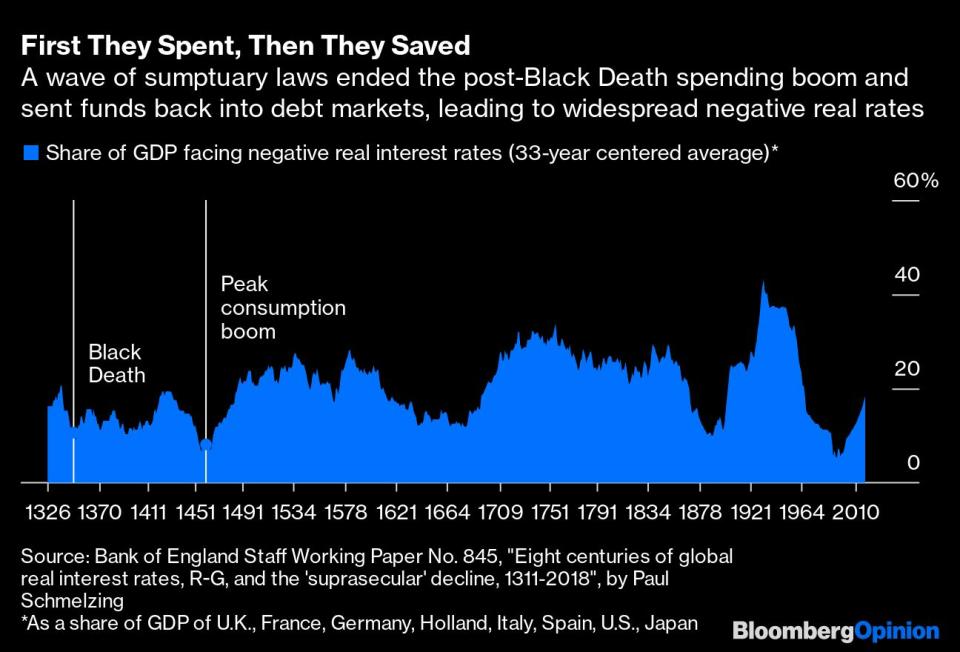

Average annual global inflation between 1360 and 1460 slowed to just 0.65% compared with 1.58% between 1311 and 1359, according to historian Paul Schmelzing’s study analyzing eight centuries of interest rates, published by the Bank of England in January. Nominal wages rose in line with productivity and to lure survivors to till the land. Dis-inflation boosted real wages.

The change in behavior was more stark. “The Black Death created not just the means for wider parts of the population for excessive consumption – but the traumatizing experience of sudden decimation in the earthly life also triggered the impetus to enjoy it to the fullest, while still able to,” Schmelzing notes.

Products that hadn’t been for mass consumption earlier — such as linen underwear and glass panes in windows — became more widely available as cheap capital rushed to satiate the growing desire to consume, according to “Freedom and Growth,” historian Stephan Epstein’s review of states and markets in Europe between 1300 and 1750. Sumptuary laws that, among other things, sought to limit the height of Venetian women’s platform shoes were the state’s way to rein in conspicuous consumption; eventually the mad spending ended and savings went to bond markets. A republican ethos was born.

An outbreak in a pre-capitalistic society has no exact parallels with today, though it does highlight some of our current challenges. The “secular stagnation” theory has blamed a hollowing out of aggregate demand over decades for the anemic recovery from the 2008 crisis. The lackluster share of wages in output may be exerting relentless downward pressure on interest rates. By laying bare the fault lines of production that rely on people to come together on buses, trains, planes and in offices and factories, the virus could hasten the age of the robot and the algorithm. Since automatons need no pay, the demand deficiency could worsen.